How should we eliminate the term “Polish concentration camps” from the media? How can we put a stop to the falsification of history and build a positive image of Poland internationally? These and many other vital questions were addressed during a conference organised by the Łukasiewicz Institute at the Sejm of the Republic of Poland. The event attracted a number of eminent guests, including Vice President of the European Parliament Ryszard Czarnecki, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs Jan Dziedziczak and President of the Polish–German Parliamentary Group Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk, MP.

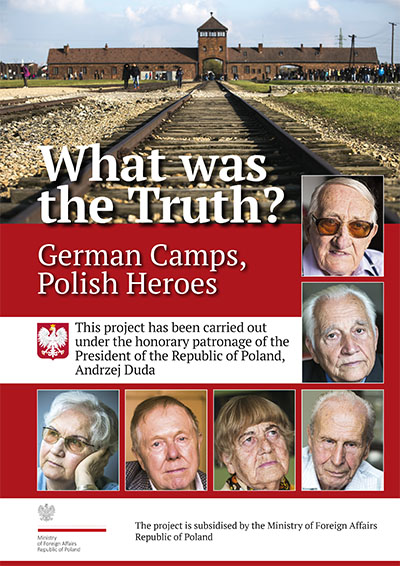

The discussion panel was organised as part of the project “What Was the Truth? German Camps, Polish Heroes” carried out by the Łukasiewicz Institute. The goal of the initiative is to promote the accounts of Polish heroism during World War II to foreign journalists. The project is carried out under the auspices of the President of the Republic of Poland Andrzej Duda.

I would like to extend a word of thanks to the Łukasiewicz Institute Foundation for their courage in addressing this vital and relevant issue, wrote Marek Kuchciński, Marshal of the Sejm of the Republic of Poland, in a letter to conference participants. The letter emphasised that there is a need for a “firm stand against mendacious and offensive phrases that are targeted against Poland”.

It has been an honour to participate in such an important conference on one of the key challenges for Poland, said Ryszard Czarnecki, Vice President of the European Parliament. I am glad to see so many experts on the issue who do care about the good reputation of Poland and the Polish nation and are keen to fight stereotypes and propaganda. Just as these stereotypes stem from ignorance, they often constitute the conscious falsification of history, he explained.

Ryszard Czarnecki also said that there is a common tendency to attribute the atrocities of World War II to the Nazis. We have to start to challenge such thinking. There was no such thing as the Nazi nation. By perpetuating such phrases, we help the Germans to wash their hands of the matter while they have every reason to repent for a long time yet.

Mr Czarnecki recalled that on the wave of protests from Polish MPs, the word “Nazis” was replaced with “Germans” in a European resolution commemorating the 60th anniversary of the liberation of Auschwitz. The pressure from the state authorities is very important, but the agreement between various opinion-forming circles in Poland also plays a part. I am really sad that some of the opinion-formers in this country, who themselves perpetrate the pedagogy of shame, are unwilling to see and name the things as they are.

It is our duty as human beings to commemorate German concentration camps in Poland and Polish people who died in the concentration camp network. I am also addressing the issue for personal reasons. My grandmother, Bronisława Czarnecka, cooperated with the Polish Council to Aid Jews, otherwise known as Żegota. I am proud of her heroic conduct during World War II. Thank you for having me here at the conference.

Jan Dziedziczak, Deputy Minister of Foreign Affairs, also expressed his gratitude to the conference organisers. We are investing in the future by dealing with the past, he said. It is vital that we showcase the true accounts of Polish history to our partners, especially these days when the role of public diplomacy has grown to be as important as more traditional diplomatic measures. Our position is a comfortable one because we do not have to spice up history. All we have to do is demand the truth.

Minister Dziedziczak emphasised that the incumbent government is running a coherent historical policy and takes opportunities to build a positive image of Poland internationally. One such window of opportunity opened with World Youth Day and the visit of Pope Francis I to Auschwitz. We have decided that the arrival of around one million young people and their shared curiosity about the world, as well a growing interest in concentration camps from the media, offer a great chance to create a true and favourable narrative about our country. In collaboration with the Institute of National Remembrance we have published a brochure in nine languages to be distributed to each and every participant in World Youth Day and all accredited journalists. The brochure provides a brief account of Polish history and a detailed discussion of the German concentration camps. Our narrative represents Poland as the first European country to have taken a stand against Hitler. It was also in Poland where Europe’s largest underground state emerged during World War II, said Jan Dziedziczak.

According to Jan Dziedziczak, one of the greatest virtues of the Łukasiewicz Institute publication is that it provides witness accounts. Concentration camp survivors see and name things as they are, he said. I am glad that your publication provides an interview with Karol Tendera, he added. An Auschwitz survivor, Karol Tendera has been awarded the badge of honour Bene Merito, the highest decoration from the Ministry of Foreign Affairs, for taking a stand against the use of “Polish death camps” by the foreign media and defending the good reputation of Poland. It is vital that NGOs such as the Łukasiewicz Institute are committed to bringing back historical truth to life. Thank you for your initiative. I am really happy to be here with you today.

Szymon Szynkowski vel Sęk, President of the Polish–German Parliamentary Group, began his speech with congratulations to the Łukasiewicz Institute. The project is a value in itself. The academic and political background only adds to its significance. The project is carried out under the auspices of the President of the Republic of Poland. Witold Waszczykowski, Minister of Foreign Affairs, and Ryszard Czarnecki, Vice President of the European Parliament, who is the most important Polish MP in the whole of the European Parliament, have also lent their support. The Łukasiewicz Institute collaborates with a number of prestigious institutions, including the Institute of National Remembrance and the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. All this adds to the importance of the initiative. I had no doubt whatsoever that the Polish–German Parliamentary Group should also become one of its partners.

Mr Szynkowski vel Sęk explained that the group conducts honest talks with German MPs on expectations concerning the narratives describing World War II. Our job is to explain to German politicians that they also should respond to each usage of ‘Polish camps’ in the media. The two sides can easily become speakers for historical truth.

Building the positive image of Poland is one of the key issues in strengthening our security and independence, argued President of the Polish Anti-Defamation League Maciej Świrski. He also added that the Polish narrative should be presented in a more effective way. Making a public display of our wounded pride and being reactive to the lies will not do much. For the last four years, the Polish Anti-Defamation League has shown how to use a politically correct language in communiques to foreign media and Western audiences. This is the only language they can easily understand, he said. He also went on to explain that the media using phrases such as “Polish concentration camps” should be stigmatised as racist, promoting hate speech, discrimination and Holocaust denial. This kind of message can actually break through to journalists to help them understand the problem. People in the West find it particularly degrading to be called racists or someone who promotes hate speech or perpetuates Holocaust denial, explained Maciej Świrski.

He said that when the Polish Anti-Defamation League was established, everybody thought that the main focus of the organisation would be on the falsification of history performed by the foreign media. However, it soon turned out that half of their activities had to be addressed to Polish audiences. ‘Pedagogy of shame’ or the ‘disdain industry’ have played a large part in this,” he explained. Both terms describe a mechanism whereby negative information on Poland first appears in the Polish media, is repeated by Western journalists and returns to Poland as a reportedly Western view of Poland. Jan Tomasz Gross and his legacy are the finest examples of anti-Polish activity.

Just the other day the Israeli daily Haaretz quoted Jan Tomasz Gross, who said that Polish people killed ca. 100–200 thousand Jews, which is obviously not true, the topic was elaborated by Mateusz Szpytma, PhD, Vice President of the Institute of National Remembrance. We should act immediately in such cases, which is why I would like to extend a word of thanks to the Łukasiewicz Institute for their campaign. Mateusz Szpytma also argued that people in the West no longer attribute the responsibility for the Holocaust to the German state. We have all heard about mythical Nazis, who are no longer exclusively German. They can be Polish. There is little awareness of the fact that right from the outset Poland was in the Allied Forces coalition, said Mateusz Szpytma.

The process of reclaiming historical truth is going to be a long-term process, just as it took many years for some people to falsify history, pointed out Senator and historian, prof. Jan Żaryn. In the absence of the Polish sovereign state, many different national elites have worked for a long time to shift the blame for concentration camps to Poland. We had no agency as a state, and we had no tools to counteract their doings. According to Senator Żaryn, the process of reclaiming historical truth requires that Polish elites undergo major transformation, as they are now dominated by people who care very little about Polish values. I know this may sound a little harsh, but that is the truth. As a matter of fact, Polish foreign policies should focus on bringing together a group of people who feel very strongly about our image abroad, are not ashamed of our history and can also serve as witnesses. This is one of the main goals of the incumbent government, he explained. Senator Żaryn pointed out that Germany is a powerful and significant player on the global political scene. Our task it to enter into a dialogue with Germany. They should become our partners in building the account of Poland and Polish people during World War II.

At the Museum, we work on a daily basis with journalists to explain their inaccuracies. We run educational campaigns, develop publications and explain why it is necessary that we call the perpetrators German instead of Nazis, said Piotr M.A. Cywiński, Head of the Auschwitz-Birkenau Memorial and State Museum. The sheer skill with which the Germans have shirked the blame for the Third Reich and the atrocities of war is just intriguing, admitted Jerzy Haszczyński, Foreign Section Manager at the Rzeczpospolita daily. He elaborated on the last ten years of the newspaper’s activity and the stand they took against “Polish camps”. One of the more tangible effects of their struggle is that the use of the phrase is prohibited by journalistic manuals at many American dailies and Associated Press, the world’s largest press agency.

I saw a note yesterday on the website of the World Jewish Congress saying that over 140 Jewish visitors got food poisoning in the ‘Polish camp at Auschwitz’. If you are a naïve reader you may just as well say it was Polish neo-Nazis who poisoned these people, said Krzysztof Wyszkowski, Member of the Board of Trustees at the Institute of National Remembrance. We need to design a suitable language to fight these pernicious phrases, said Maciej Korkuć, PhD, Head of the Bureau for the Remembrance of National Struggle and Martyrdom at the Kraków Branch of the Institute of National Remembrance. I would suggest that we try to drop phrases such as the ‘struggle against the falsification of history and Polish concentration camps’ in our discussions. Instead, we can bring back the ‘truth about German camps’. We have to make sure that these pernicious phrases do not return in the media.

However, the speakers pointed out that this approach involves certain risks: by refraining to address the stigmatiferous term openly, we allow foreign media to thoughtlessly perpetuate the phrase. One of the speakers said that the falsification of history and phrases such as “Polish camps” can be put under the heading of “defective codes of memory”. The phrase was first coined by prof. Artur Nowak-Far, Undersecretary of State in the Ministry of Foreign Affairs during Radosław Sikorski’s office.

In 2013, when the term first appeared in the media, it looked like another fancy and meaningless idea. Sadly, the phrase is still in use. In my view, the term ‘defective codes of memory’ only confuses the issue. The mendacious phrase ‘Polish death camps’ should be defined as ‘Holocaust denial’, which is punishable by law. The term is far from ideal, but it is recognised internationally, argued Maciej Świrski.

Draconian punishments were meted out for any form of resistance against the German authorities. Service to the Underground Polish State was punishable by death or deportation to a concentration camp. One of the persons affected was General Stefan Rowecki, pseudonym Grot (“Arrowhead”), the most prominent figure of the Polish Underground State and the Home Army’s founder. Soon after his capture by the Gestapo in July 1943 he was transferred to Sachsenhausen. He was tortured and repeatedly encouraged to form an alliance between the Home Army and Germany against the Soviet Union, and later, to stop the Warsaw Uprising. The General remained adamant and was eventually executed.

Draconian punishments were meted out for any form of resistance against the German authorities. Service to the Underground Polish State was punishable by death or deportation to a concentration camp. One of the persons affected was General Stefan Rowecki, pseudonym Grot (“Arrowhead”), the most prominent figure of the Polish Underground State and the Home Army’s founder. Soon after his capture by the Gestapo in July 1943 he was transferred to Sachsenhausen. He was tortured and repeatedly encouraged to form an alliance between the Home Army and Germany against the Soviet Union, and later, to stop the Warsaw Uprising. The General remained adamant and was eventually executed.